games as art

A New Way to Think about Games

What is the hour count that a game lives in your memory?

This article was originally published in March 2021 on Medium.

IN HIS VIDEO ESSAY The Future of Writing About Games, Jacob Geller proposes:

“It seems like every few months, we have the same conversation about game reviews; should they factor hour count into their assessment? ... I don’t judge my favourite TV shows on number of episodes, my favourite songs on their runtime ... I have an alternative proposition, although even more impossible to implement. What is the hour count that a game lives in your memory?”

This idea — that the quality of a game should be measured by its emotional and intellectual impact — is one that can fundamentally change how we think about games. That we measure our experiences by how much they allow us to relate, think, engage, and change.

Night In The Woods by Infinite Fall, 2017

If one looks to the indie scene over the past decade, it is clear that this concept in games is growing. Minecraft, Hollow Knight, Undertale, Night In The Woods — they all make us think. They engage us. They give us opportunities to learn about the world and ourselves. To analyse what can normally be far beyond us.

R. Alan Brooks — in a recent TED talk — said, “Go make art and scare a dictator.” Games are no different. They can give us worlds to express ourselves, characters to relate to, and concepts to think about in ways that can affect our own reality. Whether they’re as creative as Minecraft, as relatable as Night In The Woods, or as blunt as Tonight We Riot — games can be art. There’s no denying that.

If we return to the concept proposed by Jacob Geller, it can be seen that the model is almost purely subjective. However, no game is made in a vacuum. Each title is influenced by its own time, resources, and beliefs. If this is the case, then why must game journalism be constructed always purely and objectively — like it was made in a vacuum?

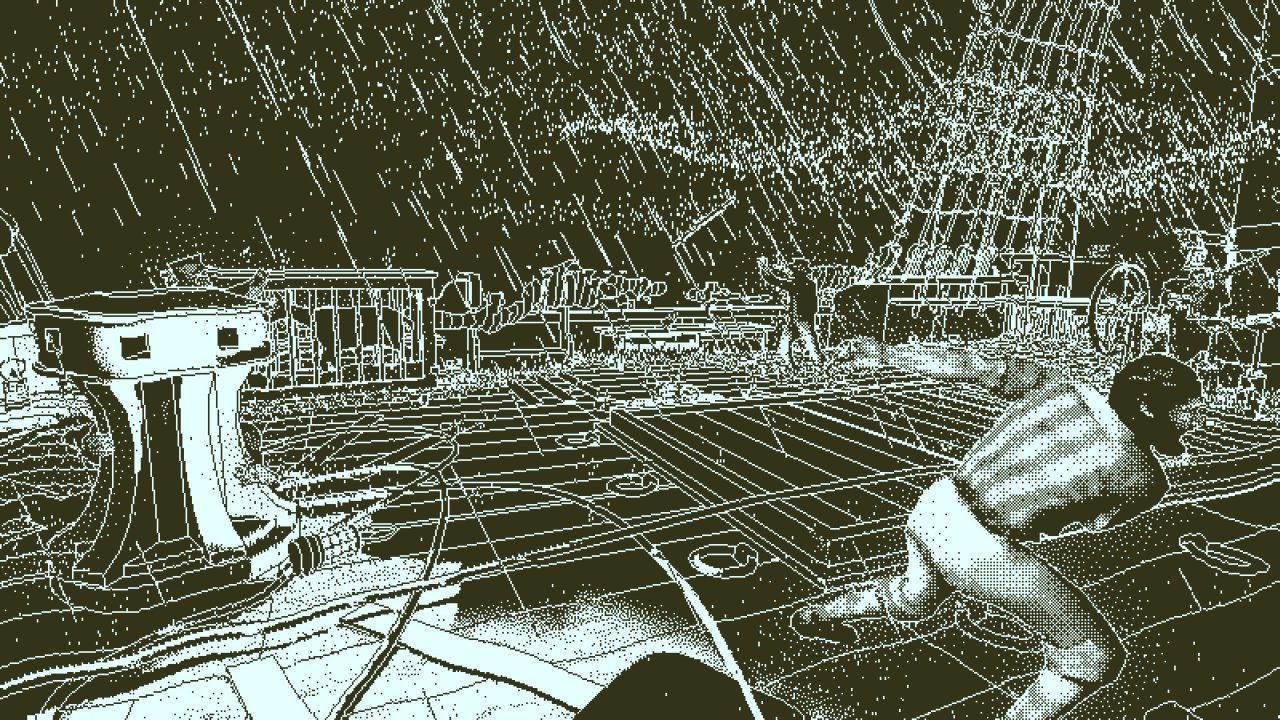

Return of the Obra Dinn by Lucas Pope, 2018

By embracing the beauty of subjectivity — the impossibility — we can view games as what they truly are — experiences. Experiences that we think about. That we can remember. That change us and shape us. After all, a game is a virtual world. And just like the real one, we can all enjoy it individually, together.

So, the next time you play, write, or think about a game, stop for a moment, and ask yourself a question.

What is the hour count that this game lives in my memory?